Consolidation and Conflict

The wave of autocratization in Asia and Oceania continues. Even India, the world’s largest democracy, has been affected, leaving its future uncertain. China has begun to reveal weaknesses in governance as it veers further away from the successful strategies of past decades. By contrast, Taiwan remains on a very steady course, and Singapore’s soft authoritarianism continues to impress.

The BTI 2024 delivers three key findings for the Asia and Oceania region. First, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the wave of autocratization that has been evident for about a decade. The easing of the pandemic and the lifting of strict virus-control measures have definitely not led to a recovery of democratic and rule-of-law-based institutions, processes and practices. The first variant of this autocratization involves so-called borderline democracies, including India, which was still in 21st place in the BTI 2006’s political transformation rankings, but has since plummeted to 50th place. The second relates to “hardening” autocracies. Their latent susceptibility to crises distinguishes both of these variants from the (largely) consolidated democracies and autocracies in the region.

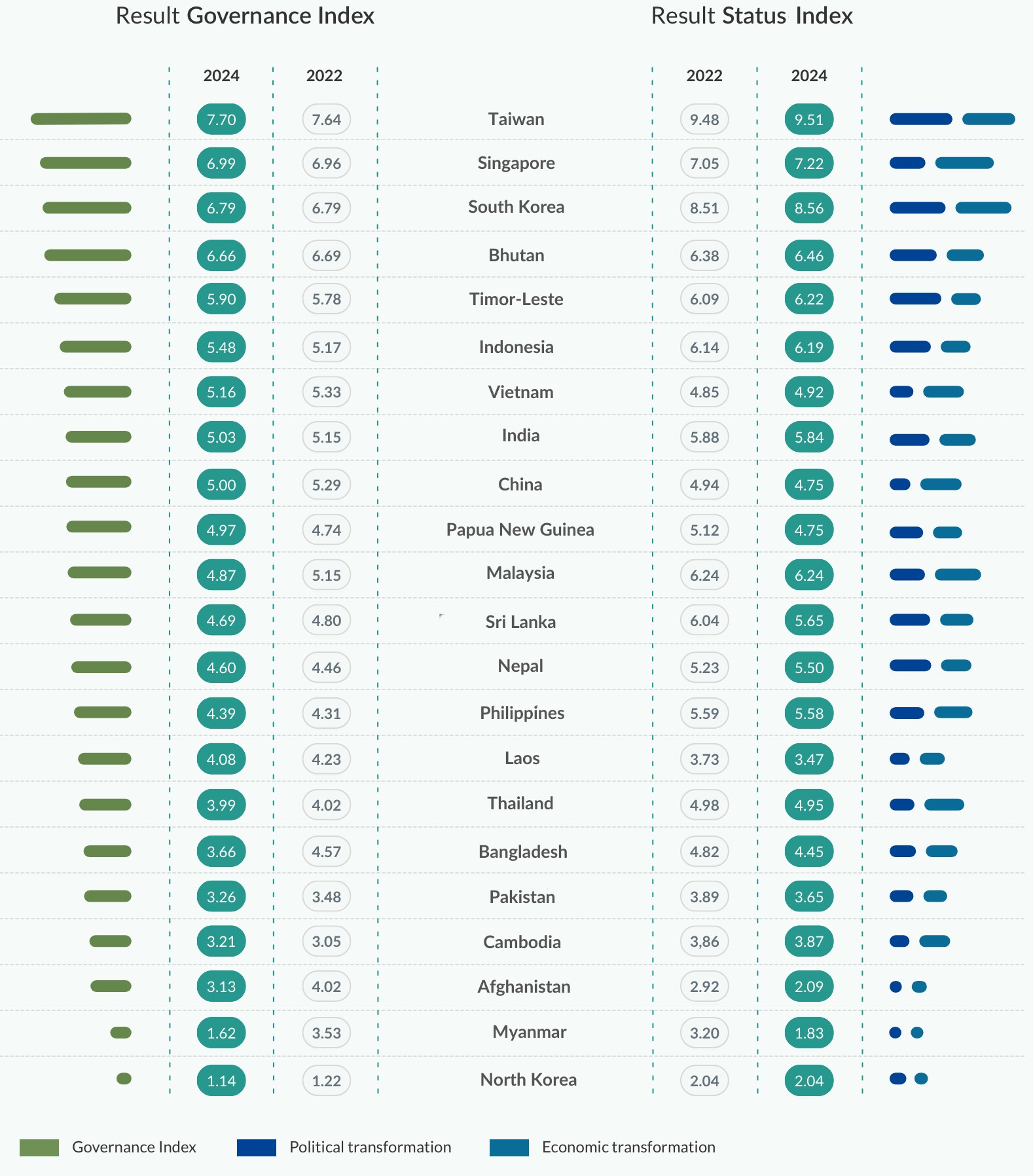

Second, most of the region’s countries have not (yet) fully recovered from the economic setbacks triggered by the pandemic. Indeed, for the region as a whole, the economic transformation trend during the BTI 2024 review period continued to point downward (– 0.13 points). Third, governance performance has also declined for the most part, with the biggest drops coming in Myanmar following the February 2021 coup (– 1.91), in Afghanistan after the Taliban re-seized power in August of the same year (– 0.90), and in Bangladesh (–0.91). However, decision-makers in China, whose pandemic-era governance was still receiving praise as recently as in the BTI 2022, also began to exhibit new or latent weaknesses in their steering capability, the apparent negative results of centralization, personalization and an ideologically driven approach to ruling (–0.30).

Political transformation

Houses of cards and latent threats

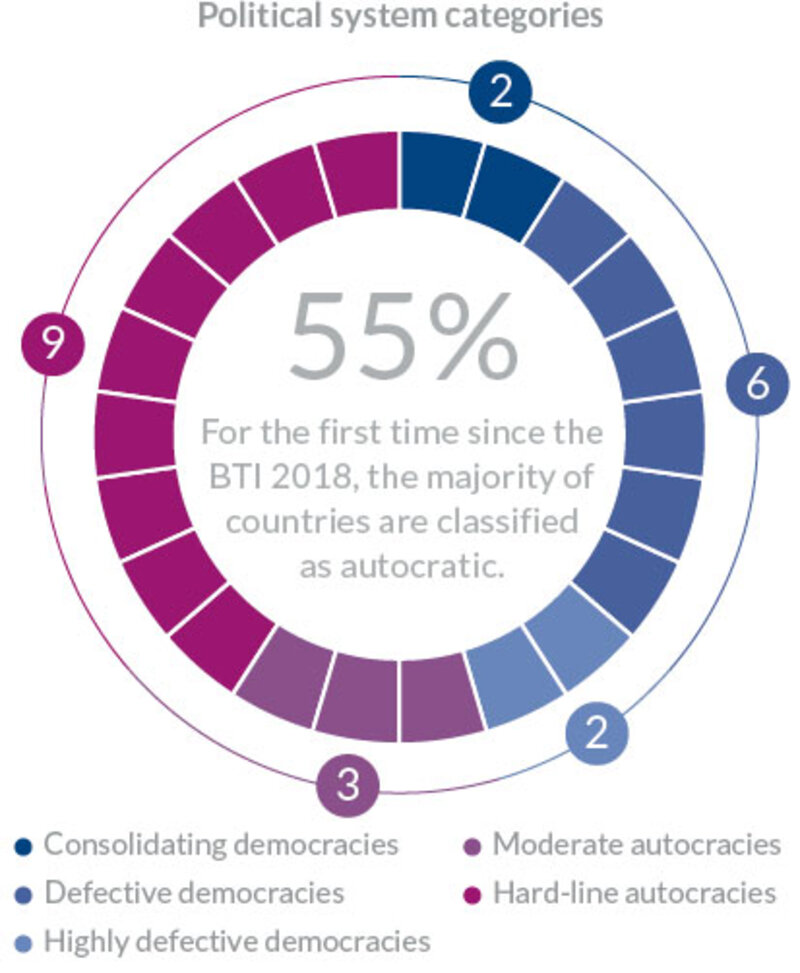

Compared to the BTI 2022, the number of democracies in the region fell from 11 to 10 during the period under review, as Papua New Guinea (–0.98 points) is no longer categorized as a highly defective democracy. This is ultimately due to administrative shortcomings in the country’s 2022 parliamentary elections. Although political violence, vote-buying and electoral authorities’ inadequate organizational capacities have been an inherent feature of every election since independence in 1975, these weaknesses have now reached an unprecedented level. In contrast, Nepal (+ 0.40) made further progress in deepening and securing the democratic reforms introduced after the constitutional crisis in the 2010s.

Of particular significance for the overall regional trend is the fact that 14 of the 22 countries have experienced a deterioration in their political transformation scores, with this being very significant in some cases. However, only five countries were able to improve the democratic quality of their political institutions and processes. This trend has produced an increasing number of borderline democracies in Asia and Oceania. All of these have been exhibiting a downward tendency for years, bringing them increasingly closer to the group of already clearly authoritarian political systems, with even the minimal conditions for democracy being subject to massive strain. As a result, the democratic systems of government in these countries increasingly resemble fragile “houses of cards” that could collapse at any time. The BTI 2024 counts four such borderline cases: India, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. All three borderline cases in the BTI 2014 – Bangladesh, Papua New Guinea and Thailand – have today become authoritarian systems.

Bangladesh and Thailand now belong to a second category of political systems displaying a negative dynamic: the group of hardening autocracies. These are polities that were previously less repressive or even minimally democratic but have become increasingly repressive over the last decade or so and have now assumed a clearly authoritarian character. This group also includes Afghanistan, Cambodia and Myanmar. In contrast to the consolidated autocracies, in which all politically significant groups recognize the autocracy’s core political institutions and follow its rules (whether out of conviction, fear or self-interest), the hardening autocracies cannot always rely on the general acceptance or at least widespread apathy of their subjects and semi-loyal elites. However, these systems have not yet become so repressive that all traces of civil rights and political freedoms appear to be simply faded memories or distant illusions. This results in a persistent, at least latent threat to the regime, which is the main driver behind its hardening process. The fact that the state’s monopoly on the use of force is the only indicator within the political transformation dimension to have improved in almost all cases in this group since the BTI 2014 is not necessarily good news. This shows that these states are becoming both more assertive and more repressive in the course of their authoritarian hardening.

Economic transformation

Economies suffering from long COVID

The COVID-19 pandemic has also left a clear mark on the region’s economies. The positive development of the previous decade, which had been running counter to the slow downward global trend, is now a thing of the past. While the region’s average economic transformation score in the BTI 2020 was 5.72, it is now only 5.34. In the most recent review period, the monetary and fiscal stability criterion was hardest hit overall (–0.39). But sustainability, as it relates both to environmental and education policies, also suffered significant losses (– 0.14).

A comparison of economic performance after the coronavirus crisis with performance in the BTI 2020 also shows how differences within the region have widened. Improvements are only evident in Singapore and Taiwan, countries that have long displayed a high level of economic transformation. In contrast, almost three-quarters of the region’s countries suffered a decline in this area. The worst performer is Myanmar, where the combination of the pandemic, a military coup, prolonged civil resistance and a resurgence of ethnic violence have wiped out a decade’s worth of development progress in just two years’ time. However, performance in Sri Lanka and Laos has also shown an extremely steep decline. Overall, no country at an already-low transformation level managed to improve in this area after the pandemic. That said, in Papua New Guinea’s case, the country’s dependence on global demand for raw materials, which was a disadvantage during the COVID-19 crisis, has now proved to be an advantage thanks to the recovery in demand and rising commodity prices. However, this growth has done little to benefit the broader population, as can be seen from the fact that almost a quarter of Papua New Guinea’s residents is considered undernourished.

Comparing India and China, the region’s two economic powerhouses, is also revealing. In terms of economic performance, even though India is still two points below its 2020 level, it has recently been one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. This contrasts sharply with trends in China. There, although the score for economic performance is just one point lower than in the BTI 2020, the economy’s annual growth rate of just 3.0 % is by no means sufficient to meet pressing challenges, such as youth unemployment, demographic change and rising levels of inequality. This is primarily due to the disastrous consequences of a series of repeated pandemic-era lockdowns, which led to a cascade of nationwide protests in November 2022. These are also partially responsible for the high youth unemployment rate, which reached a record level of 19.9 % in June 2022.

Governance

Strong men, weak governance

While the region’s average score for the Governance Index fell again, by 0.19 points as compared to the BTI 2022, reaching just 4.65 points, transformation management in Taiwan remains very strong. In fact, the island takes first place in the overall ranking – even though the heightened tensions between Beijing and Taipei have been accompanied by an increase in polarization between the political camps, with the closely linked issues of national identity and relations between Taiwan and mainland China taking center stage. Singapore is another good or even exceptional example. Although the People’s Action Party, which has been in power since 1959, shows no inclination to permit expanded democratic freedoms, the city-state actually tops the BTI rankings in terms of steering capability and resource efficiency.

At the other end of the governance spectrum, Bangladesh is a negative standout (–0.91). Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wazed’s Awami League government, which has been in office since 2009, seeks to legitimize its course by pointing to economic growth, rising incomes, infrastructure development and the fight against terrorism. However, it is increasingly facing a crisis of performance and distributional disaffection in all these areas. The government has not made the restoration of democratic practices a priority. Nor does there seem to be any willingness to engage in genuine dialogue with the opposition or civil society organizations. In Myanmar’s case, the government experienced an outright collapse in steering capability following the military coup in 2021. The region’s country experts are only more critical of North Korea for this criterion.

In the BTI 2024, Indonesia regained some of the governance quality it had previously lost under President Joko Widodo (“Jokowi”), who has been in office since 2014. Like Vietnam and India, the country now ranks ahead of China in this area. However, a comparison of India and China shows that such shifts do not always indicate an actual improvement in government performance. In both countries, respectively under strongmen Narendra Modi (prime minister since 2014) and Xi Jinping (president since 2012), the quality of governance has been declining, although this downward trend was even more pronounced in China than in India during the BTI 2024 review period. Nevertheless, this should not obscure the fact that Modi is jeopardizing the longstanding foundations of India’s democratic institutions at the national level. By transforming the country’s secular democracy into a Hindu ethnocracy, his Bharatiya Janata Party risks squandering India’s greatest comparative advantage relative to China.

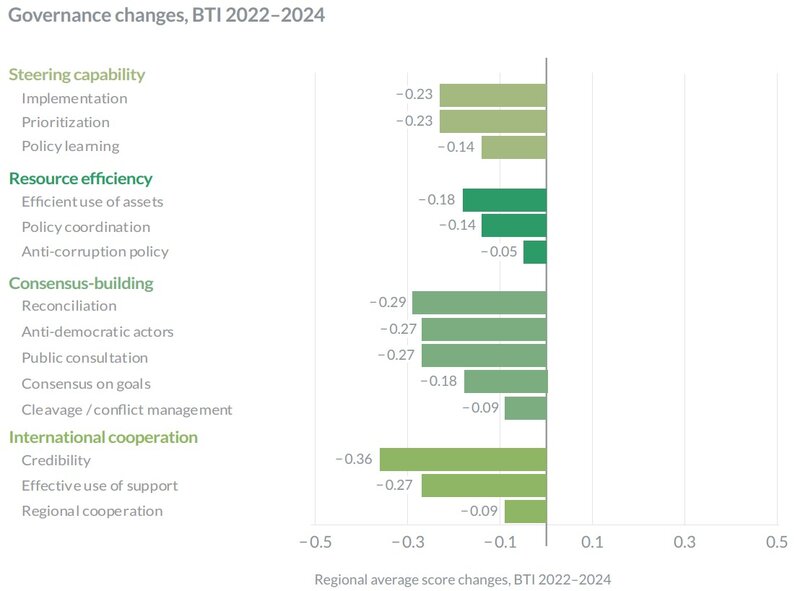

In the region as a whole, international cooperation between states (–0.24), consensus-building capacities (–0.22) and policymakers’ steering capabilities (–0.20) have seen the greatest downward slides. The declining willingness to cooperate is observed in Beijing’s tendency to pursue an increasingly confrontational course in geopolitical matters, a development viewed by many with concern, as well as the military junta of Myanmar’s deep isolation and the impact of the domestic crisis on relations within ASEAN. The Taliban’s takeover in Afghanistan and the Bangladeshi government’s declining credibility and reliability are also having a negative impact. With regard to Afghanistan, the seemingly moderate decline of 0.90 points should not lead to the false conclusion that the Taliban “might not be as bad” after all. In truth, the government they toppled was already characterized by woeful governance – unlike, for example, the hard-working, albeit often unsuccessful government of Aung San Suu Kyi, the state counselor of Myanmar, before that country’s coup on February 1, 2021.

Outlook

Between failure and fortitude

As in previous years, the BTI offers little cause for optimism regarding the Asia and Oceania region. The weakening of democratic freedoms, rights, processes and institutions by actors at the center of political power structures (“endogenous” autocratization) continues to be the predominant form of authoritarian transformation. In this respect, this region is similar to most others around the world. Nevertheless, it is striking that the military coup in Myanmar and the Taliban’s victory in the Afghan civil war have again given substantial significance to older forms of “exogenous” autocratization that were dominant during the Cold War.

At present, the future of India’s democracy is highly uncertain. However, while the current trend is undoubtedly moving in the direction of ethnocracy, the resilience of the country’s federal system should not be underestimated. The ongoing autocratization is not transforming all regions and individual states to the same degree. Instead, it is affecting different population groups in different ways, and it is having particular impact on specific facets of the constitutional democracy while leaving others (almost) untouched. This is indicated, for example, by the fact that the integrity of (national) elections remains robust. Developments in Sri Lanka and Thailand are also far from clear.

And then there is the case of China. If the Communist Party clings to the agenda promoted by President Xi Jinping, who has recently reversed many of the measures that made economic development possible in the almost four decades since modernization began, it will be difficult to regain the country’s lost momentum. China’s competition with the United States adds a further complication, as the latter is increasingly making demands on the other countries in the region regardless of their relationship with the People’s Republic.