In the shadow of war

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine is leaving its mark on the countries of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. While the aggressor has fully shifted into a hard-line autocracy, the victim has effectively mobilized substantial resistance bolstered by Western support. Amid these developments, several countries have suffered indirect repercussions while others are reaping economic rewards. Ultimately, the outcome of the conflict will shape the region’s prospects in the long run.

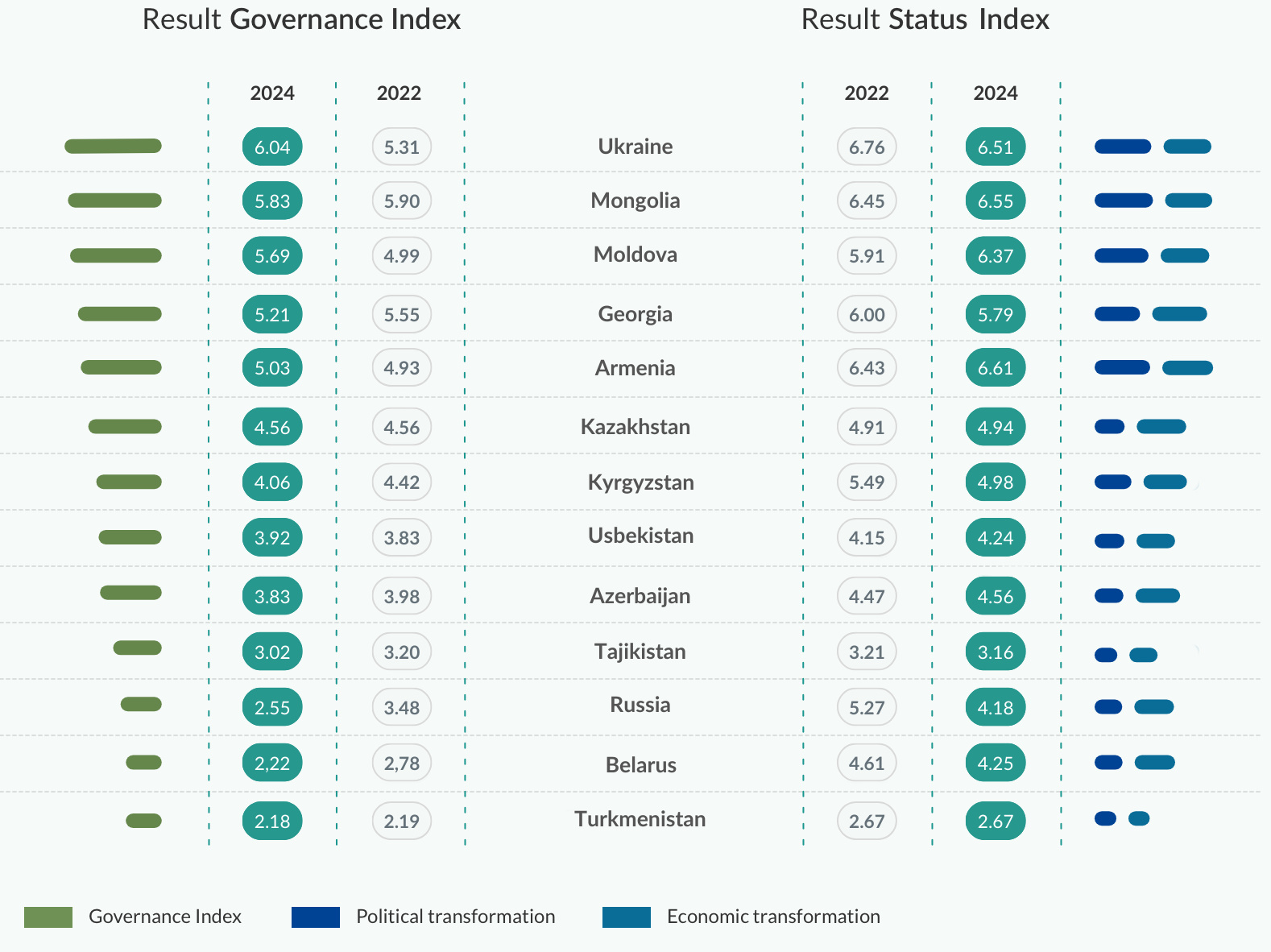

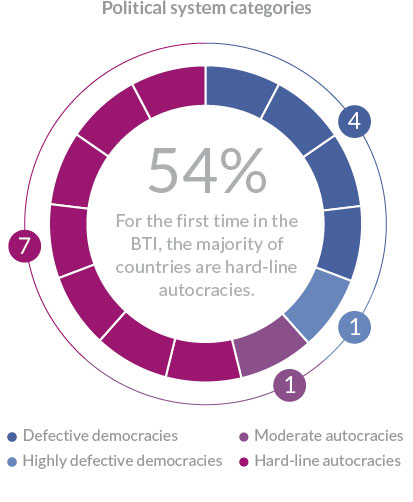

The moderate upward trend that distinguished the region encompassing Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia in previous BTI reports (2018 –2020) from global developments has since lost steam, a development that can be largely attributed to a single factor: Russia’s war against Ukraine. Russia, which recorded some of the largest declines of all BTI countries in its democracy status score (– 0.97 points), its economic transformation status (–1.21) and the Governance Index (– 0.93), is also the primary driver of declining average scores across all three BTI dimensions for the entire region. Now classified as a “hard-line” autocracy characterized by “failed” governance, Russia ranks only marginally ahead of the region’s usual poor performers, namely, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. Following a similar trend, the worsening state of transformation in Belarus has only solidified.

In contrast to these developments, we see the target of this orchestrated aggression demonstrating remarkable resilience. Despite enduring significant economic setbacks (index score: – 0.75), Ukraine has made substantial gains in its democracy status (+0.25) and, even more remarkably, in its Governance Index score (+0.73). Given the imposition of martial law in February 2022 and the mobilization of Ukrainians to counter Russia’s attack, these accomplishments, which continue to hold, impress all the more. It’s worth highlighting that two other democracies, Armenia and Moldova, have succeeded in consolidating or even improving their positions despite facing considerable external pressure. Georgia and Kyrgyzstan, on the other hand, continue their downward trajectory, with the former now classified as a “highly defective” democracy and the latter as a “moderate”. autocracy. At the same time, they number among the economic winners of the war, as they are able to take advantage of unanticipated market opportunities, Russian favors and positive migration effects.

Political transformation

Dreams of accession and matters of succession

The region’s democracies are the only states that have shown any progress during the current review period. Armenia, where domestic policies are heavily impacted by the threat emanating from neighboring Azerbaijan, recorded only relatively modest improvements in terms of political transformation (+ 0.15). Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, who, against all expectations, achieved a clear electoral victory in 2021, has struggled to implement his reform agenda amid the ongoing conflict with the country’s neighbor to the east.

Early parliamentary elections held in 2021 in Moldova (+ 0.55) resulted in a surprise, historic electoral victory for the liberal, pro-European alliance Action and Solidarity (PAS), which presented Moldova with the opportunity to be classified as a candidate for accession to the EU on June 23, 2022, alongside Ukraine. This, in turn, triggered a wave of protests orchestrated by the party of the fugitive, pro-Russian ex-oligarch Ilan Shor until it was banned by the Constitutional Court in June 2023.

Pro-Russian sympathies are no longer prevalent in Ukraine. In addition to the immense supply of foreign aid to Ukraine, the combined impact of an existential threat and mass societal mobilization account for the diminished power of oligarchies in the besieged country, which has facilitated the gains made in judicial reform and anti-corruption efforts (+ 0.25). Georgia, which also applied for EU candidate status in March 2022, received instead a list of 12 “recommendations” from the European Commission. The Commission’s call for “de-oligarchization” targets the not-so-subtle influence of Bidzina Ivanishvili, while its call to “depolarize” domestic politics may be an appeal to Mikheil Saakashvili’s supporters.

At the same time, nearly all of the region’s autocratic regimes are contending with the challenge of planning for the transition of power. Kazakhstan was the first during the review period to grapple with this issue. President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev seized the opportunity to strip his predecessor, Nursultan Nazarbayev, of his positions of power in the wake of violent protests. Nonetheless, Nazarbayev continued to exert influence from behind the scenes. In early presidential elections held in November 2022 and parliamentary elections in March 2023, Tokayev won by a comfortable margn, thereby receiving a mandate to replace Nazarbayev’s networks with his own.

In Uzbekistan, a similar approach was taken when Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who had long served as the prime minister under Islam Karimov, assumed office – though he did so only after Karimov had passed – which initially disrupted the influence of the ruling family clan. Having opted to follow the Putin model of extending his term to the maximum limit, Mirziyoyev has secured his future until at least 2037. The seemingly safest path has been taken by Turkmenistan’s Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, who designated his son Serdar as his successor in March 2022. After Serdar signaled his intention to pursue a different form of governance, Gurbanguly initiated further parliamentary reforms and now presides over a single-chamber parliament with almost unlimited powers of oversight.

In Russia, as well, where Vladimir Putin’s current term is slated to conclude in 2024, the stability of the regime depends heavily on the person who created it. While Putin’s victory is predetermined, the sham elections will also serve as a staged plebiscite for the war.

Economic transformation

From survival mode to profiteering from crisis

The war has also triggered economic upheaval, with the most pronounced effects being felt in Ukraine. In 2022, the country’s economic output plummeted by more than 30 %, pushing unemployment rates to 36% (according to unofficial estimates). The poverty rate currently exceeds 24% and, by early 2023, the country registered more than 5.3 million internally displaced persons. In addition, some 8.25 million Ukrainians were registered as refugees in Europe at the beginning of 2023. According to World Bank estimates, nearly $ 411 billion in funds will be needed to address the damages incurred after only a year of war. Considering the devastating nature of this situation, Ukraine has displayed remarkable resilience, which has been buoyed by a level of bi- and multilateral support not seen since the Marshall Plan in the wake of World War II, when adjusted for inflation.

Russia, on the other hand, faces unprecedented punitive measures. While sanctions have missed their mark in the short and medium terms, Russia faces substantial economic challenges. Official figures have been released only sporadically since the spring of 2022, but the country’s automotive, aviation and tourism sectors are clearly suffering downturns. Russia’s energy sector, which accounted for two-thirds of all exports in 2022, is the economy’s key stabilizing factor. While those tasked with managing the Russian economy strive to contain the damages, members of Putin’s inner circle, known as the “siloviki,”

view the country’s growing detachment from the West as an opportunity. They are willing to accept the deepening dependence on China that this entails. Russia’s economy is increasingly determined by geopolitical factors.

There are also a number of countries in the region that have directly or indirectly benefited from the war. Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan, for instance, have reaped the benefits of elevated commodity prices. In principle, this applies to Kazakhstan as well, which sought to expand its market share within the EU as a consequence of the war. However, to ensure the continued flow of its oil exports, the country relies on the Russian Black Sea port of Novorossiysk, but Moscow has repeatedly denied access to it.

In contrast, Georgia is benefiting directly from the war, much like Armenia, and is engaged in a delicate balancing act, which is gradually deepening the country’s dependence on Russia. For example, the country has welcomed tens of thousands of Russian war emigrants while abstaining from supporting anti-Russian sanctions and positioning itself as a transit nation for “parallel imports.” At the same time, Georgia has strategically exploited the void left by the departure of Western companies from the Russian market.

We see a counterexample in Moldova, which has taken in large numbers of Ukrainian war refugees without recording any “parallel exports,” even though it did not join the EU sanctions regime until the spring of 2023. In the fall of 2022, Moldova’s opposition, aligned with Russia, aimed to exploit this delicate situation to further destabilize the government. The authorities in Chisinau would have faced significant challenges countering this objective without assistance from the international community. Nonetheless, the country recorded improvements in five indicators and the strongest regional increase (+ 0.36) for economic transformation status.

Governance

A second duel with troubling ramifications

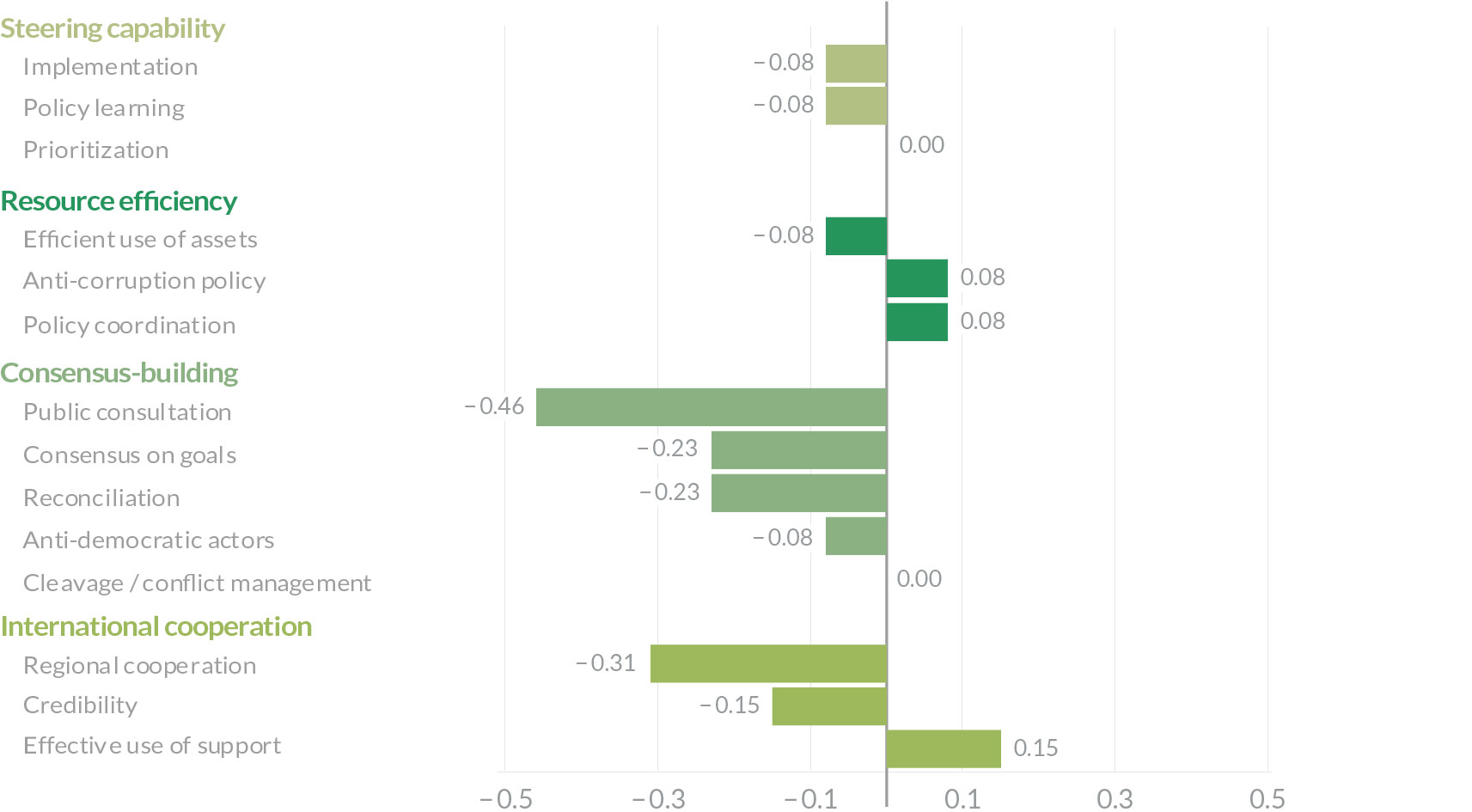

Developments in the quality of governance across the region are similar to those witnessed in political transformation. Here, we see in particular governance performance among the region’s autocracies deteriorating. This is specifically evident in the case of Russia. Its governance effectiveness largely centers around its capacity for repression and sanctions management. We see clear downward trends in Belarus, as well (– 0.55), where Alexander Lukashenko is waging a de facto war against his own population. Kyrgyzstan is also falling behind (– 0.36) and is now classified among the countries demonstrating “weak” governance. President Sadyr Japarov’s authoritarian-populist governance style uses social media and populist rhetoric to legitimize his opportunistic goals and illiberal measures.

In Moldova and Ukraine, the prospect of EU accession granted in mid-2022 has injected a clear sense of purpose, goals and coherence into their transformation processes. The prospect of EU membership for Ukraine is based on the EU’s aim to demonstrate solidarity with the country’s wartime sacrifices and the need to avert the resurgence of another gray zone, especially as Europe confronts the possibility of renewed division. Ukraine’s most significant economic achievements so far have revolved around the market-oriented adjustments it has introduced, which are essential for trade with the EU.

In Moldova, the president, government and parliament have aligned together in favor of reforms. In a departure from the past, this has enabled close and effective operational coordination with external partners. However, since 2022, the country has been in a state of continuous crisis, which complicates the achievement of reform goals as much as the fact that a significant portion of the administration’s staff lacks substantial experience with working in government. In addition, persistent internal resistance, fueled by Moscow, adds another layer of challenges.

Developments in the quality of governance across the region are similar to those witnessed in political transformation. Here, we see in particular governance performance among the region’s autocracies deteriorating. This is specifically evident in the case of Russia. Its governance effectiveness largely centers around its capacity for repression and sanctions management. We see clear downward trends in Belarus, as well (– 0.55), where Alexander Lukashenko is waging a de facto war against his own population. Kyrgyzstan is also falling behind (– 0.36) and is now classified among the countries demonstrating “weak” governance. President Sadyr Japarov’s authoritarian-populist governance style uses social media and populist rhetoric to legitimize his opportunistic goals and illiberal measures.

In Moldova and Ukraine, the prospect of EU accession granted in mid-2022 has injected a clear sense of purpose, goals and coherence into their transformation processes. The prospect of EU membership for Ukraine is based on the EU’s aim to demonstrate solidarity with the country’s wartime sacrifices and the need to avert the resurgence of another gray zone, especially as Europe confronts the possibility of renewed division. Ukraine’s most significant economic achievements so far have revolved around the market-oriented adjustments it has introduced, which are essential for trade with the EU.

In Moldova, the president, government and parliament have aligned together in favor of reforms. In a departure from the past, this has enabled close and effective operational coordination with external partners. However, since 2022, the country has been in a state of continuous crisis, which complicates the achievement of reform goals as much as the fact that a significant portion of the administration’s staff lacks substantial experience with working in government. In addition, persistent internal resistance, fueled by Moscow, adds another layer of challenges.

Outlook

The end of the gray zone?

Russia’s war in Ukraine is reverberating both politically and economically across Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. The outcome of the war is expected to shape the face of this region for a long time. While countries like Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan have reaped economic benefits from Moscow’s efforts to bypass Western sanctions and the resulting emigration of numerous citizens due to war and mobilization, this contrasts starkly with the severe setbacks suffered by Ukraine and, indirectly, Moldova. The fact that their chances of joining the EU have significantly improved in the long shadow of the war is a political gain with longer-term implications. For Armenia, the balance sheet is adverse, with its economic gains from the war overshadowed by Russia’s weakening influence and the fact that Azerbaijan has managed to strengthen its hand through its militarized diplomacy vis-a-vis Armenia.

For Russia, finding itself increasingly entangled due to its anti-Western stance in a situation it regards as existential, the outcome appears to be preordained. According to the new Foreign Policy Doctrine of March 2023, Russia now embodies an independent Eurasian and Euro-Pacific “state civilization.” Behind this is the reactivation of the civilizationalism that is anchored in Marxist-Leninist ideology.

The war thus poses a significant risk of cementing a division within the region. What began as a competition for integration through the EU Association Agreements and the establishment of the Eurasian Economic Union has morphed into a confrontational dynamic demanding strict loyalties. The resulting military assurances through mutual deterrence from NATO on one side and Russia on the other will shape the political options available to states in the region and thus narrow their options in terms of foreign and domestic policy.

Whether neighboring countries can – or want to – escape Russian advances remains uncertain. This uncertainty is amplified by the fact that an even more potent autocracy, China, is making its presence felt in the region and promoting a concept of transformation more or less aligned with that of Russia. Now more than ever, those countries resistant to these pressures require a level of support that the EU and NATO have only provided cautiously to date. If Russia prevails and polarization becomes entrenched, the gray zone navigated thus far by Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova and Ukraine may vanish.