Less democratic, less successful

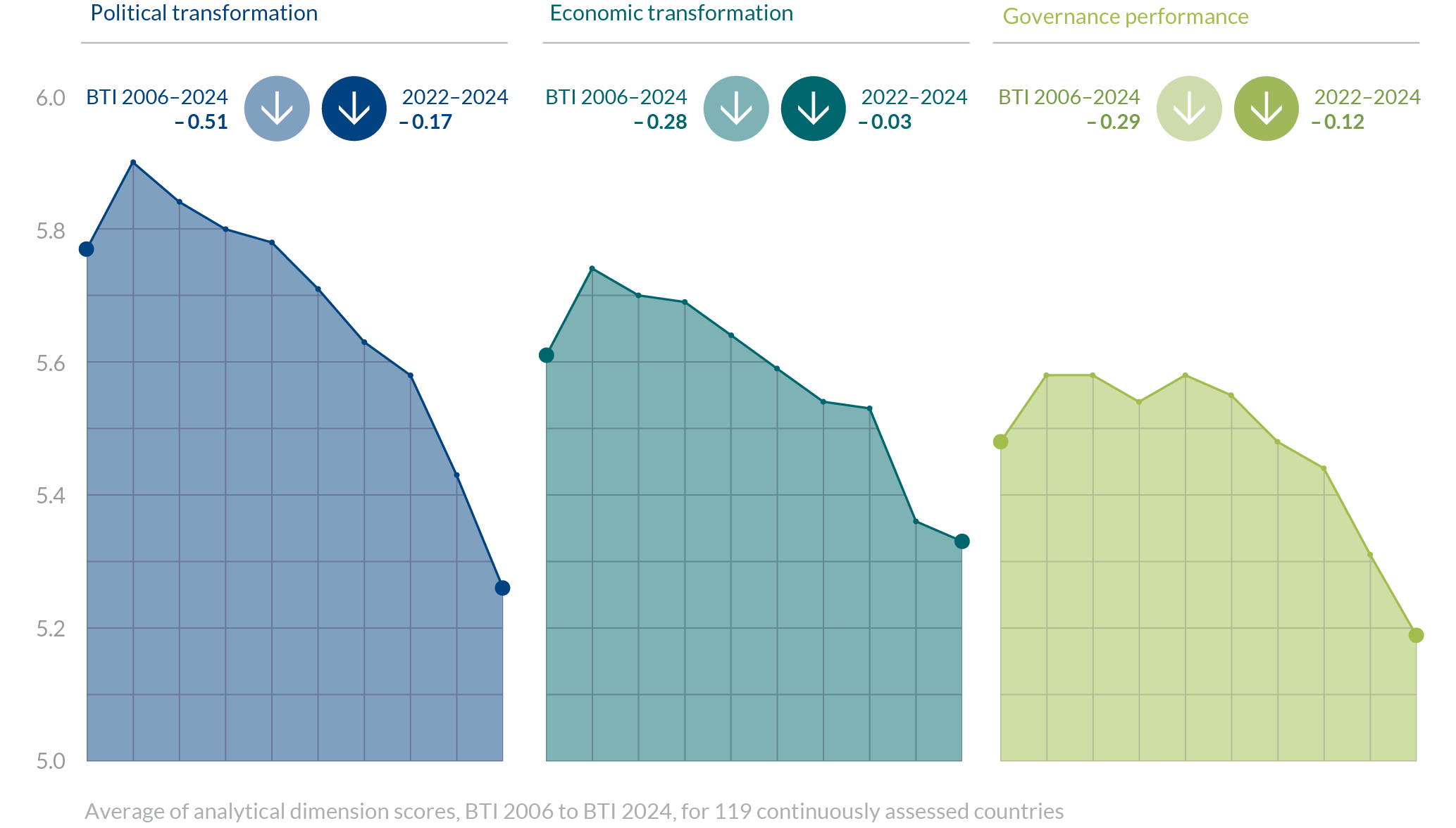

This edition of the Transformation Index records an unprecedented rise in the number of poorly governed states. The BTI 2024’s Governance Index presents a gloomy global picture, with the quality of governance and the ability of states to advance the norms of a constitutional democracy and an inclusive market economy hitting a new nadir, registering a mere 4.60 points on average. Until the BTI 2018, the cohort of countries featuring very good or at least good governance consistently made up at least one-third of the survey sample. However, in the BTI 2024, this group, which includes countries as diverse as top-scoring Taiwan and lowest-scoring Côte d’Ivoire, has dwindled to just over a quarter. Once again, more than 100 countries are now assessed as featuring “moderate” to “failed” governance.

During the period under review (February 2021 through January 2023), we observed a noticeable decline in the ability of some governments to consistently implement their self-defined priorities and effectively manage available resources. We also witnessed international cooperation suffer further blows in terms of credibility and reliability. The capacity or willingness to fend off anti-democratic elements, either through steadfast exclusion or astute engagement with obstructive political forces, diminished most drastically during this review period. In a growing number of countries, advocates of democratic and market-oriented reforms are finding themselves marginalized as opponents who favor alternative approaches ascend to positions of influence.

This deteriorating state of governance is closely linked to a similar decline observed in political transformation. The erosion of checks and balances undermines executive accountability, while restrictions on political participation make it increasingly challenging to critique government policies. Instances of the abuse of office, corruption and mismanagement often go unpunished, perpetuating a culture of impunity. Among the 137 countries surveyed by the BTI, 74 are presently under the grip of some form of authoritarian rule in which political participation is either prohibited or permitted to a minimal extent. However, even within several democracies, we see public discourse subject to increasing manipulation and restrictions, reflecting an illiberal drift toward authoritarianism. The erosion of trust in democratic institutions and processes is yet another consequence of poor governance.

These adverse trends in governance and political transformation have unfolded in a context of worsening economic conditions that are rooted in Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which has driven up food and energy prices and added more fuel to post-pandemic inflation in many countries. At the same time, it’s important to consider the worsening state of economic transformation in the broader context of its relationship to poor governance. Many governments are either unwilling or unable to adopt sustainable and socially inclusive economic policies over the long term. Instead, their efforts are geared toward sustaining a corrupt system of patronage that hinders both free and fair economic competition.

Political transformation - Coups and increasingly tighter grips on power

Over the past two years, the global landscape of political systems surveyed by the BTI has seen yet another noticeable shift, with autocracies further gaining ground and democratically governed countries facing setbacks. Today, 74 developing and transition countries, comprising a populace of four billion individuals, are under autocratic rule, while 63 states, with a collective population of three billion, adhere to democratic principles.

In this BTI edition, the ongoing trend of political regression is largely due to regime changes, coups and the entrenchment of autocracy in countries like Belarus, Russia and Türkiye. Among the 19 states grappling with substantial setbacks in political transformation, only three are democratically governed. In Mauritius, Peru and South Africa, the rise of patronage systems, corruption and polarization is eroding the effectiveness of political institutions.

The BTI 2024 once again documents a concerning trend that has significantly shaped the trajectory of democracy in recent years: deliberate efforts to undermine the authority of oversight bodies such as the judiciary, legislature, regulatory agencies and the media. This inclination is facilitating the concentration of power within the executive branch and undermining the principle of separation of powers. During the period under review, it has primarily been increasingly authoritarian heads of state who have criticized efficiency shortcomings and championed a strong executive as a solution to corruption and reform backlogs. In countries such as Benin, El Salvador, Guinea-Bissau, Kyrgyzstan and Tunisia, which were classified as democracies until the BTI 2022, changes made to electoral law, judicial reforms and constitutional amendments have culminated in the consolidation of autocratic power structures.

The potential for efforts to violently overthrow governments persisted and intensified, particularly in West Africa. Military-staged coups against governments under civilian leadership or with civilian participation took place in Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Myanmar and Sudan. In addition to coup attempts in Gambia and Guinea-Bissau, we saw the Taliban emerge victorious in Afghanistan, dynastic succession take place in Chad and, following the period under review, further upheavals in Gabon and Niger.

In many countries, the setbacks observed stem primarily from the erosion of political participation rights such as free and fair elections, association and assembly rights as well as the freedom of expression. Once again, we see that the space for public engagement in political affairs has contracted substantially. Elections in 25 countries are less free and fair, while assembly rights in 32 states have been increasingly curtailed and the freedom of expression in 39 countries has faced heightened constraints. Conversely, positive developments remain rather rare and are only recorded in around a dozen countries for each category.

Almost a third of all the countries surveyed recorded the lowest level of political participation opportunities ever measured in BTI history. This poor showing is particularly palpable in numerous Arab states, such as Egypt, Sudan and Syria, where an unprecedented level of repression stifles any incipient form of political opposition. The suppression of dissent is similarly extensive in other regions and countries as well, such as Afghanistan, Belarus, Chad, Iran, Nicaragua and Tajikistan. These countries each score two or less points for the political participation criterion, indicating nearly closed societies. However, even in defective democracies, we see a narrowing scope of political participation, an increasingly compromised electoral process (e.g., Hungary), the growing harassment of critical media (e.g., India) and dissenting organizations facing tighter limitations on their activities (e.g., Serbia).

Nonetheless, amid these challenges, the BTI 2024 identifies a group of 28 democracies that are able to ensure inclusive and responsive political participation processes. Notably, the Republic of Moldova has entered this cohort for the first time, under the leadership of President Maia Sandu. Dedicated to dismantling oligarchic control, her administration has implemented measures aimed at substantially broadening participation opportunities within the country. Half of these participatory democracies have consistently maintained their high level of democracy over the past two decades, despite the transformation challenges they face. This group of resilient states includes countries across Latin America (e.g., Chile, Costa Rica and Uruguay), Caribbean states like Jamaica, EU members (e.g., Czechia, Estonia, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia and Slovenia), as well as Botswana, South Korea and Taiwan. In addition, countries such as Honduras, Kenya and Zambia have managed to reverse the trend of political regression through recent elections. Guatemala also succeeded in this regard, albeit after the end of the review period, while new governments in Brazil and Poland have been presented with opportunities to strengthen democratic institutions in their countries.

Overall, however, the short- and long-term trend, particularly concerning core democratic institutions such as political participation and the rule of law, continues to point downward, posing an increasing threat to the stability of these institutions overall. The only areas not subject to this negative trend in recent years are aspects of stateness (e.g., monopoly on the use of force) as well as those related to the engagement of civil society in policymaking processes.

In many cases, civil society emerges as the final and most resolute line of defense against the growing trend of autocratization. In Kenya and Zambia, pressure from civil society actors played a pivotal role in ensuring fair and transparent elections, while efforts to mobilize the public in protecting civil and social rights proved successful in Poland and Sri Lanka. In addition, civil society actors in the Baltic states, Czechia and Poland demonstrated their solidarity with Ukraine and war refugees. It’s remarkable that discontent with governments continues to break out even under the most repressive regimes. This was seen, for example, in the protracted protests against China’s zero-COVID policy, the demonstrations by Iranians against that country’s regime following the death of Mahsa Amini, and the protests against the military government in Myanmar.

Economic transformation - Sluggish recovery, inflation and rising inequality

The massive pandemic-era contraction of the global economy was followed by a return to growth, although this recovery ultimately proved weak compared to the scale of the preceding downturn. Following a decline in the global average score from 5.88 to 5.20 points in the last BTI, the corresponding output strength indicator saw only a slight recovery in this edition, to 5.32 points. Twenty countries even showed deteriorating economic performances, with 13 of them continuing the negative trend observed two years ago. This decline was particularly pronounced in the destabilized states of Myanmar and Sri Lanka, as well as in the warring nations of Russia and Ukraine.

For a number of countries, this halting recovery came at a time of deep fiscal policy dysfunction. While the pandemic did lead to revenue declines and necessitated additional health and social expenditures, the dire budgetary conditions in many states cannot be solely attributed to these additional burdens. Many countries were already deep in debt beforehand, with some even nearing the point of sovereign default. Argentina, Lebanon and Pakistan’s mounting debt burdens can be attributed in part to imprudent debt policies influenced by clientelism. The BTI 2024 clearly indicates that these three countries, as well as 36 other countries with four or fewer points for the fiscal stability indicator, have pursued incoherent budgetary policies that fall far short of achieving fiscal stability. After output strength, fiscal stability is the economic indicator to have seen the second-greatest decline over the past decade, with an average global drop of 0.70 points.

Inflationary tendencies during the review period resulted in part from the sharp rise in demand as many economies reopened their economies after gradually overcoming the pandemic. The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 further increased this inflationary pressure by pushing up commodity prices. Nevertheless, most governments or their central banks reacted flexibly and adaptively, countering the inflation with gradual interest rate increases. A total of 88 countries were assessed as pursuing sound monetary policy, which in the BTI 2024 corresponds to a rating of seven or more points.

By contrast, other countries – such as Lebanon, Sudan, Türkiye and Zimbabwe – recorded inflation rates in 2022 that in some cases reached into the triple digits. Acting on the instructions of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the Turkish central bank even lowered that country’s interest rate, with the goal of stimulating investment. The resulting high rates of inflation led to considerable domestic social costs, as well as a significant loss of confidence internationally. The Turkish example illustrates the extent to which narrow, personalized governance can lead to a systemic loss of learning ability and thereby to misguided economic policies.

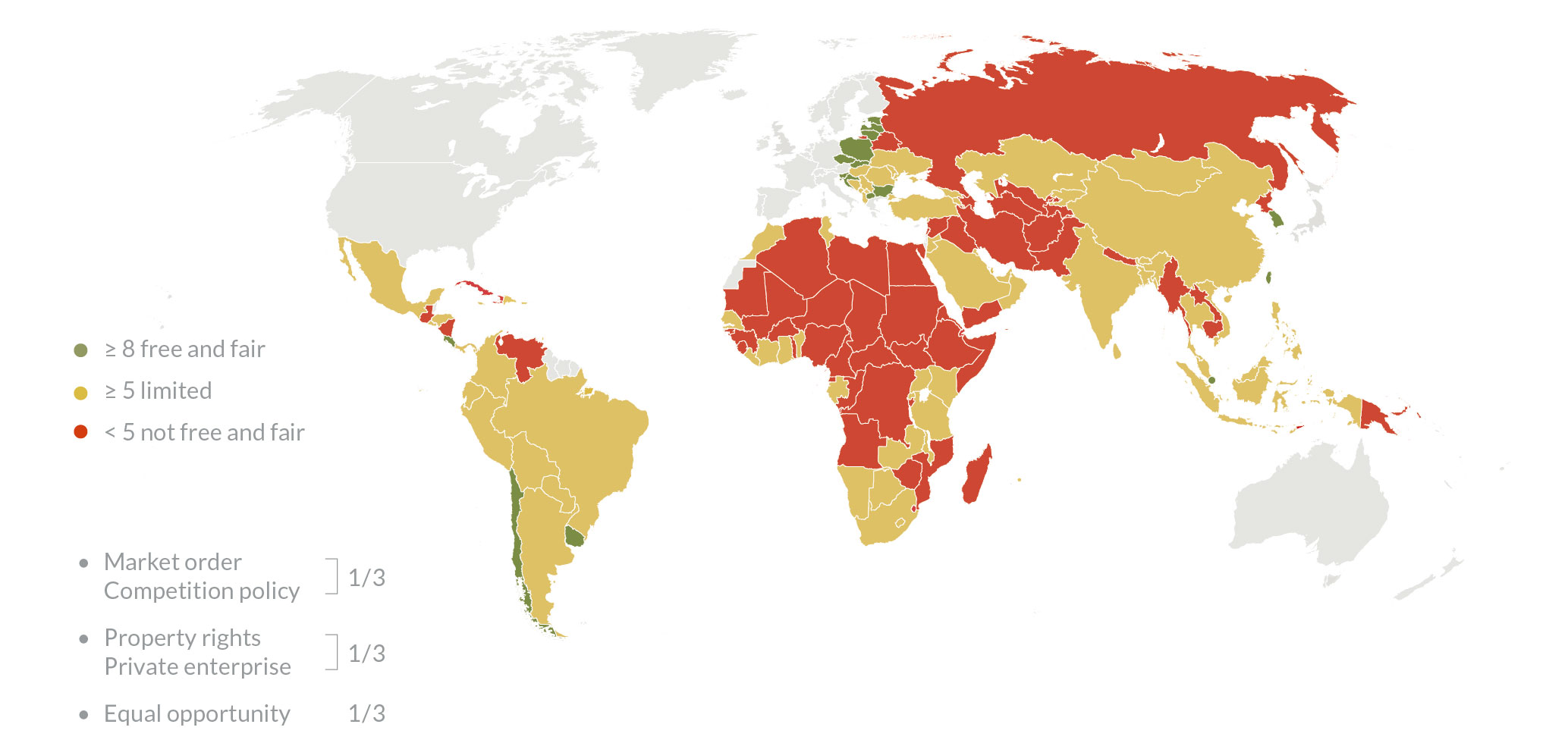

In addition to economic weaknesses and misguided economic policies, the transformation toward socially inclusive and sustainable market economies is also hindered by economic systems that fail to guarantee either fair economic participation or an equitable distribution of resources. To create fair conditions for market competition, states must provide rules allowing for fairly organized markets, robust competition policies, protections for private property, legal guarantees for private enterprise, and equal opportunities. The BTI shows that governments in the overwhelming majority of countries do not see themselves as drivers of overall social development in this way, but rather as representatives of particular interests within deliberately unfair economic systems.

Participation in economic competition is possible without restriction in only 16 countries, and with partial restrictions in 66. In roughly 40% of the countries assessed by the BTI, competition-distorting regimes hinder free and equitable access to markets. These governments fail to ensure adequate protection against price-fixing and the dominance of monopolies or cartels, and do not provide a reliable legal framework for the protection of private property. Within this selection, the indicator for equal opportunity garners by far the lowest global average score (5.01 points), with a total of 80 countries either achieving or falling below this score. In these countries, women and members of specific ethnic, religious or other demographic groups face massive discrimination in terms of their opportunities for economic participation.

The distribution of regimes within these groups of countries illustrates the strong correlation between restrictions on political freedoms and the lack of economic fairness. Among the 55 countries whose economic regimes are neither free nor fair, only five are democracies: Lebanon, Nepal, Niger, Sierra Leone and Timor-Leste. Conversely, among the 16 countries that feature virtually unrestricted economic freedom and treat all market participants fairly, Singapore is the only autocracy.

Brazil, India, Poland, Serbia and South Africa have also experienced significant declines with regard to economic freedom and fairness, although not quite on the scale of the losses observed in Türkiye and Hungary. Ten years ago, all of these states were regarded as consolidating or only slightly defective democracies. However, the boundary between state and economy has in recent years become increasingly blurred in each as a result of increasing political regression. In any case, the lack of progress toward greater economic participation implies that upholding or consolidating power within a select elite often takes precedence over the establishment of a more open and inclusive economic order.

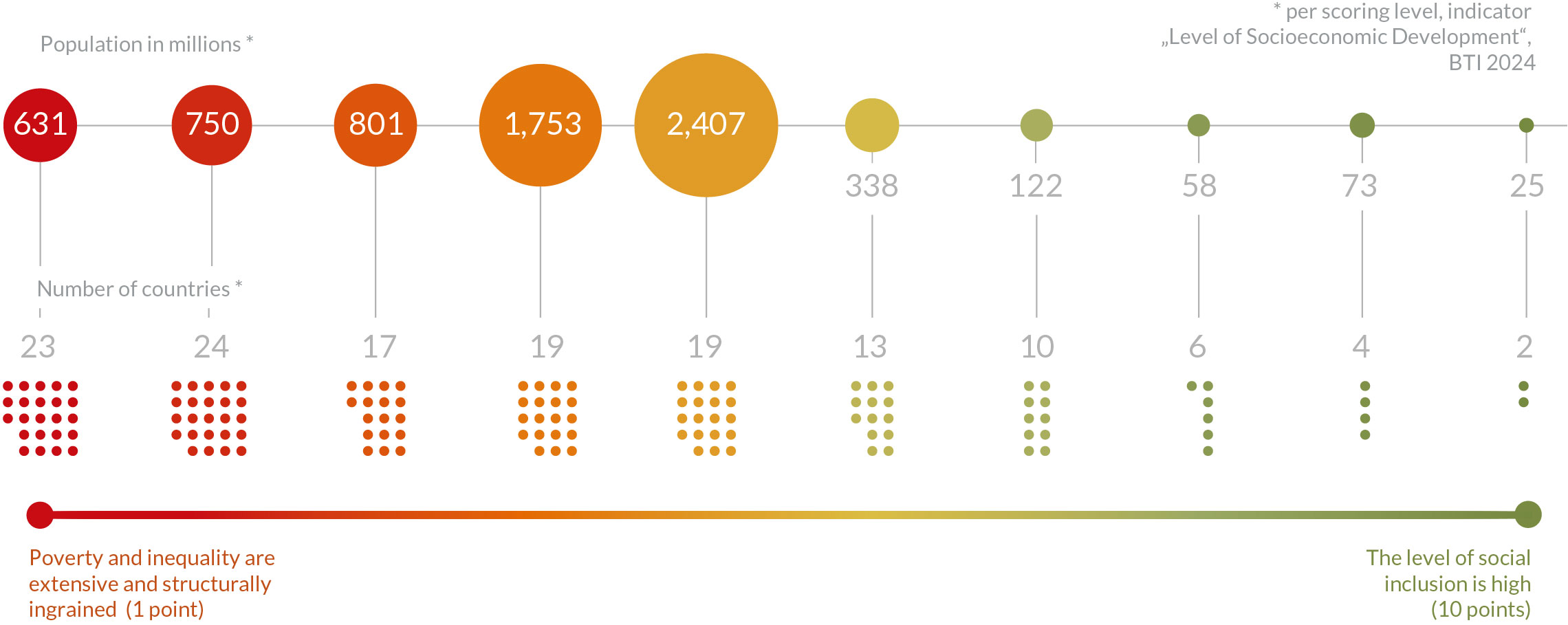

This has an impact on the level of socioeconomic development, as well as on the extent of poverty and inequality. Only a quarter of democracies, and not even one in 10 autocracies, achieve a level of socioeconomic development sufficient to ensure a relatively high degree of social inclusion. This means that widespread and deeply rooted social exclusion currently persists in 83 out of the 137 BTI countries.

Among the 50 African countries surveyed, 36 fall into the two lowest rating levels, and are marked by very high poverty rates and extreme inequality. In addition to growing inequality, poverty rates are also rising significantly again after having temporarily fallen in the years before the COVID-19 pandemic. Globally, the average level of socioeconomic development has declined to a record low of 3.98 points.

Governance - Concentration of power undermines competence

Good governance demands capable policy management that sets long-term priorities for the development of society as a whole and then implements them in an adaptive manner. It is characterized by efficient, coordinated and corruption-free leadership, and has the ability to facilitate consensus on societal development goals and defuse conflicts that arise. At the international level, well-governed countries act reliably, credibly and cooperatively. Good governance of this nature is possible even under authoritarian rule. For example, the city-state of Singapore has been demonstrating this for many years, as have the Gulf states of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, and to a lesser extent Benin and Côte d’Ivoire. However, these are the only autocracies that number among the 36 countries deemed to exhibit very good or good governance in the BTI 2024.

In recent years, a narrative has taken hold that is today being propagated with increasing intensity. According to this account, it is above all authoritarian states that are able to set and implement clear development goals without being hampered by party bickering and institutional obstructions. It is authoritarians that can efficiently notch success after success due to their tightly centralized coordination and provide for national unity and international distinction with a firm hand. Wrapping themselves in this narrative, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in Egypt and Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman in Saudi Arabia declare themselves to be successful modernizers. China and Rwanda portray themselves as developmental role models, and heads of state acting in increasingly authoritarian ways justify abolishing the separation of powers even in democracies. The general susceptibility to this narrative derives largely from the long years of cronyism and mismanagement that have plagued defective democracies, even if the track record of authoritarian-minded leaders – as in El Salvador or Tunisia – cannot justify the dismantling of democracy.

Overall, a full one-third of the governments surveyed are unwilling or unable to plan and implement societal development measures in a comprehensive and inclusive manner and to shape them in a flexible and adaptive way. Only four of these 44 countries are democracies, which means that this group includes more than half of all the regimes classified as autocracies in the BTI 2024. This is due to the fact that numerous autocratic regimes, from Belarus to Uganda, as well as post-coup states such as Burkina Faso, Mali and Myanmar, have hardened further. The progressive concentration of power in these autocracies means that decision-making is taking place in ever-narrower elite circles, often with personalistic governing styles. This, in turn, diminishes governance competence, as decision-makers are deprived of the ability to weigh alternative proposals, consider critical voices, and evaluate the policies and processes already in place.

China’s zero-COVID policy, which led to economic slumps and supply bottlenecks, illustrates this kind of behavior and its consequences. Its failure had systemic causes. Under Xi Jinping, the Chinese regime is increasingly morphing from a system of one-party rule into an absolutist monocracy. The country’s former policy learning strengths are weakening. Meritocracy in China is suffering from the fact that loyalty has now become more important than qualifications when it comes to filling senior positions. This is resulting in policy mistakes such as the overly hesitant intervention in the real estate crisis, or the draconian and ultimately unsuccessful pandemic policy.

But steering capability is also on the wane in democracies. This can be seen in southern Africa, for example, where Botswana, Namibia and South Africa all used to be members of the BTI’s top governance group. For some time, it has been clear there that long and uninterrupted terms in office are blurring the lines between the states and the governing parties, rendering the states susceptible to nepotism and corruption.

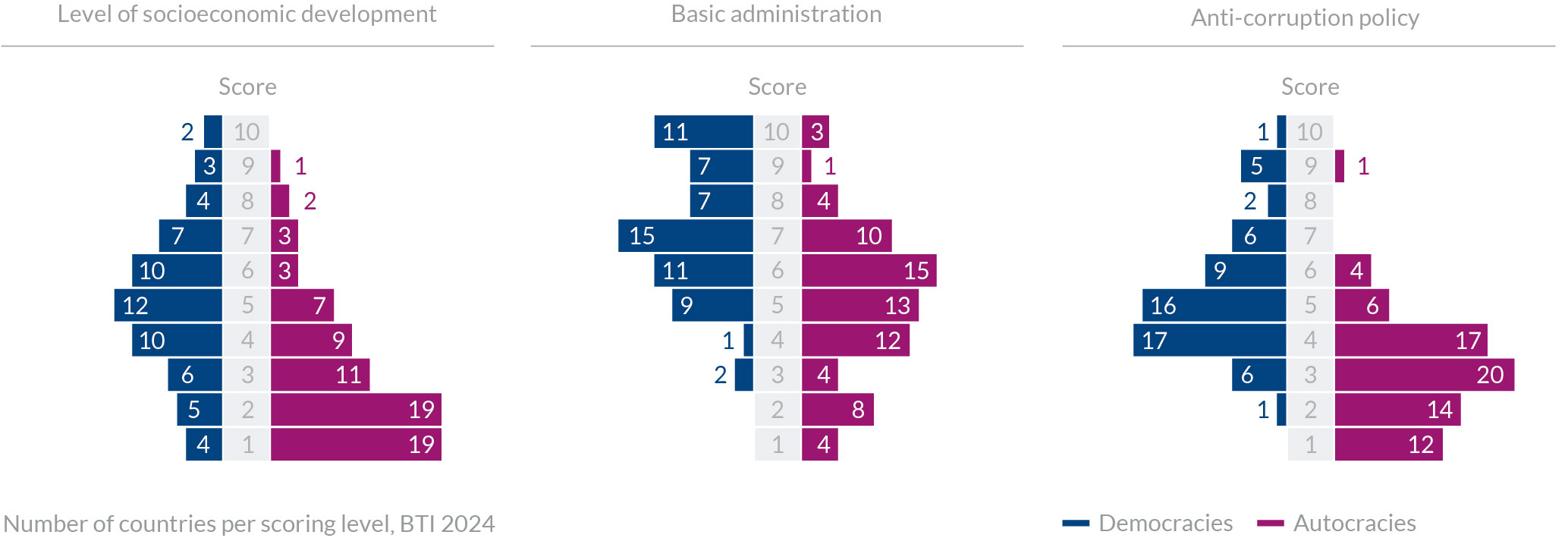

In general, there are considerable differences between the 63 democracies and the 74 autocracies in terms of government resource efficiency. For example, as a global average, the quality of policy coordination in autocracies lags far behind that of democracies (-1.54 points). Autocracies’ use of available resources is significantly less efficient (-1.88), and the gap between the quality of anti-corruption policies in the two types of system is particularly wide (-2.20). It can thus be seen that strict authoritarian governance does not offer an advantage in terms of efficiency, despite these regimes’ supposed ability to act more quickly and decisively.

However, a few exceptional authoritarian states do function efficiently. This group includes the strategically prudent city-state of Singapore, the two Gulf states of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, and, to a considerably lesser extent, Rwanda. This contrasts with 24 democracies that show a high degree of efficiency. At the bottom of the scale are 45 disorganized, wasteful and corrupt regimes, all of which – with the exception of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Honduras, Kenya, Lesotho and Lebanon – are ruled autocratically.

Authoritarian governance structures, widespread socioeconomic marginalization, inadequate administration and services, and widespread corruption all prove to be closely correlated. However, it is precisely this failure to combat corrupt structures that exposes autocratic states’ promises of efficiency as an ideological façade for a form of governance lacking any concern for fairness or inclusion. In fact, within the group of 15 governments that have shown a genuine commitment to fighting corruption, and which have established successful integrity mechanisms, Singapore is the only autocracy. On the other hand, among the 87 governments that are unwilling or unable to curb corruption, and which thus receive a score of four or less for the BTI 2024’s anti-corruption indicator, 63 are autocratically ruled. A staggering 85% of all autocratic regimes lack the authority, capability or even intention to combat opaque structures of self-enrichment and patronage.

Little willingness to defuse conflicts within society

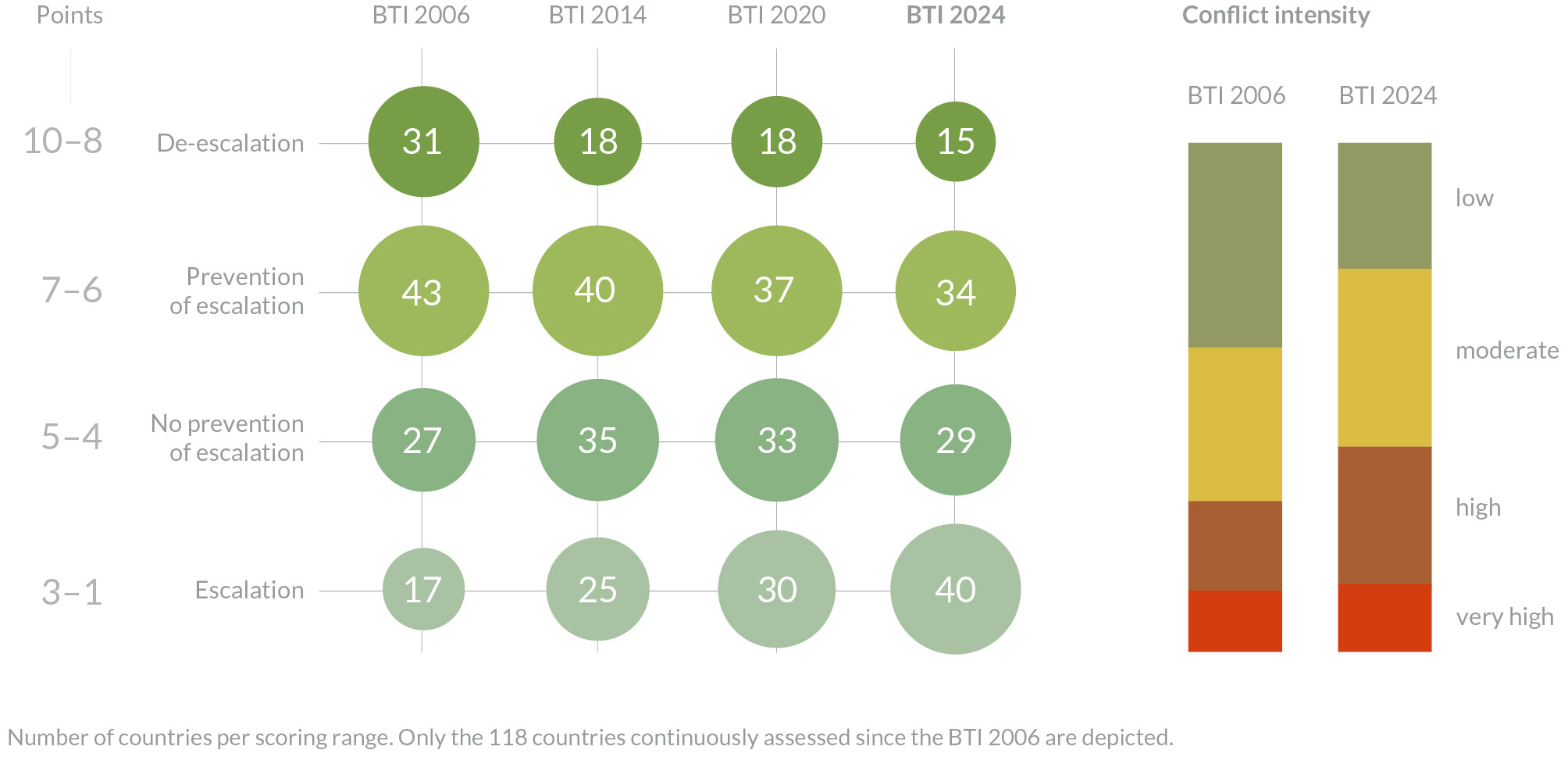

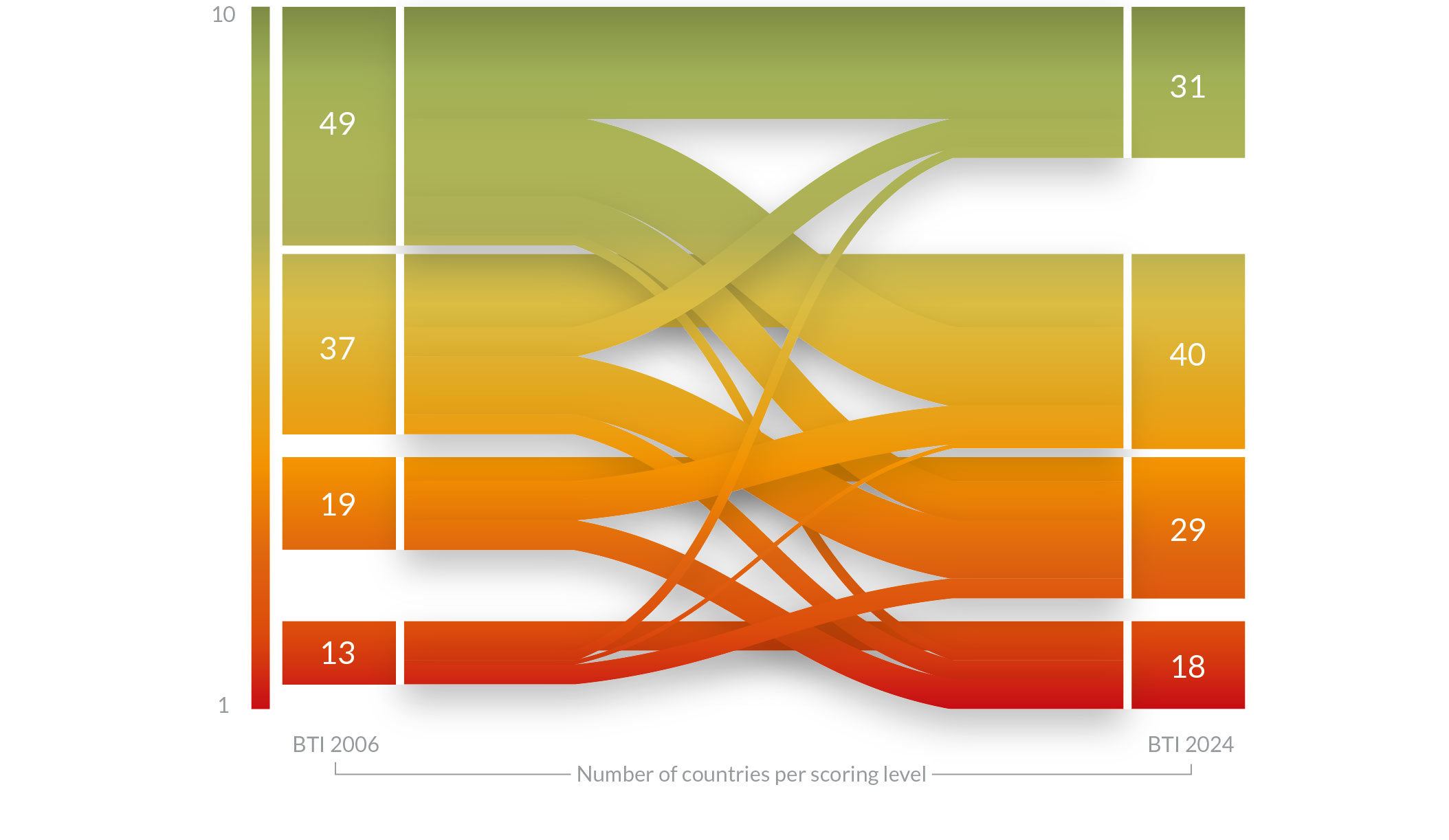

The curtailment of political participation rights, deliberate polarization as a strategy of rule, and the perpetuation of unfair and marginalizing economic systems are almost always accompanied by an intensification of political, social, ethnic and/or religious conflicts. Across all states assessed by the BTI since 2006, the score for the conflict intensity indicator has increased by a global average of 0.78 points. Over the past two years, conflict intensity has risen in 39 countries; as such, among all the negative Governance Index trends, this has affected the largest number of countries.

To date, the political classes’ reaction to this increased propensity toward violence and escalation of domestic conflicts has been woefully insufficient. It is imperative that political leaders prioritize more inclusivity, balanced consensus-building and responsiveness. Yet the results of the BTI 2024 indicate that a majority of governments have again failed to ramp up efforts in precisely these areas.

This is most evident in the assessment of political actors’ capability to engage in effective conflict management. Viewed as a global average, no other aspect of governance has seen such significant deterioration over the past two decades.

The scale of this decline can be illustrated by examining the relative share of countries that either succeed in active de-escalation or are at least able to prevent further polarization, on the one hand, compared to those that fail to prevent escalation or even actively fuel intra-societal conflicts, on the other. This ratio has shifted significantly since the BTI 2006, when 74 governments could be viewed as successful mediators, in contrast to the present count of just 49. At the same time, the number of active polarizers has increased from 17 to 40 countries. This latter group includes not only the world’s most repressive regimes, but also the populist or nationalist governments in Brazil (under Bolsonaro), Hungary, India and Türkiye, all of which are or have been governed by figures with a confrontational and authoritarian leadership style.

As a rule, all indicators associated with consensus-building are included in the negative conflict-management trend. As governments become less able or willing to defuse conflicts, the consensus on transformation goals also erodes, civil society tends to be less involved in political decision-making processes, and anti-democratic veto actors tend to gain influence.

The rising intensity of conflicts and the inability or reluctance to defuse tensions and foster consensus at the national level mirrors a troubling trend of increasingly noncommittal, uncooperative and confrontational conduct on the global stage. Domestic polarization and repression, coupled with nationalist aggression toward the outside world, are two sides of the same authoritarian coin. Notably, the governments responsible for the most significant setbacks in international cooperation are without exception the most fervent proponents of political regression. The friend-foe mentality of polarizing regimes, which stir up conflicts in order to consolidate power within their borders, spills over into a foreign policy marked by nationalism and transactionalism and following the law of the jungle. During the review period, perhaps the most glaring example of this trend was observed in the Russian regime, which launched a war of aggression on Ukraine, flagrantly violating international law and resorting to ruthless brutality. In addition to the imperialist claims postulated by Putin himself, a key motivator for this invasion was probably also the regime’s fear that a thriving democratic neighbor could serve as a countermodel to its authoritarian system at home.

Fears of external destabilization also compelled Burkina Faso and Mali, following military coups, to adopt a self-isolating, confrontational stance toward Western nations, international organizations and even the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which urgently called for the agreed-upon democratic norms to be respected. After the end of the review period, both countries found more allies among coup leaders in Niger and secured Russian support. Meanwhile, the Sudanese military junta faced even greater isolation, enduring sanctions and international censure, including from the African Union, as it systematically sidelined civilian authorities. Similarly, the military regime in Myanmar also found itself isolated on the global stage. After seizing power following electoral defeat, it resorted to severe repression in response to pro-democracy protests.

On a qualitatively different scale, yet marked by equally notable declines, are the cases of Argentina, Bangladesh, El Salvador, Peru and Tunisia, which have all been demonstrating a lack of both willingness and ability to engage in international cooperation. Here, too, domestic policy deficits are reflected in foreign policy behavior. Argentina, for example, grapples with an ideologically charged and consistently unreliable Peronist foreign trade policy, mirroring the polarizing and opaque domestic approach of the government recently voted out of office. Similarly, the authoritarian government of Bangladesh faced severe censure from the United Nations and the Biden administration in the United States due to its troubling practices of abduction, extrajudicial killings and torture as well as the glaring absence of accountability for such violations. Meanwhile, in El Salvador, the foreign policy of President Bukele continued to show disregard for the rule of law and human rights by violating the Inter-American Democratic Charter, to which his country is a signatory. The internal gridlock stemming from a polarized government, with tensions between the executive and parliament, hindered Peru’s ability to engage effectively in international cooperation. Furthermore, the Tunisian government, characterized by a highly personalized leadership under President Saied, displayed inflexibility and diplomatic limitations. These factors have, in turn, led to a significant reduction in U.S. support, primarily due to a decline in credibility.

These governments represent the most recent drivers of an increasingly pronounced long-term trend, namely, the erosion of international cooperation and multilateral conflict management. In contrast to the other governance criteria, whose ratings have mainly worsened over the past decade, the willingness to engage in international cooperation has been steadily deteriorating from a previously high level for two decades. Overall, however, international cooperation is still the best-rated governance criterion. While steering capability, resource efficiency and consensus-building are rated below five points on average globally, the international cooperation criterion still stands at over six points despite significant losses, especially in terms of reliability and credibility.

In this context, the importance of good governance cannot be overstated, and it entails more than merely ensuring participatory, equitable and socially inclusive societies. On the national level, it plays a pivotal role in restoring and reinforcing trust in democratic institutions. And, on the international level, it is a key factor in securing the cooperative and peaceful solutions we need to address long-term global challenges.