Increasingly autocratic and assertive

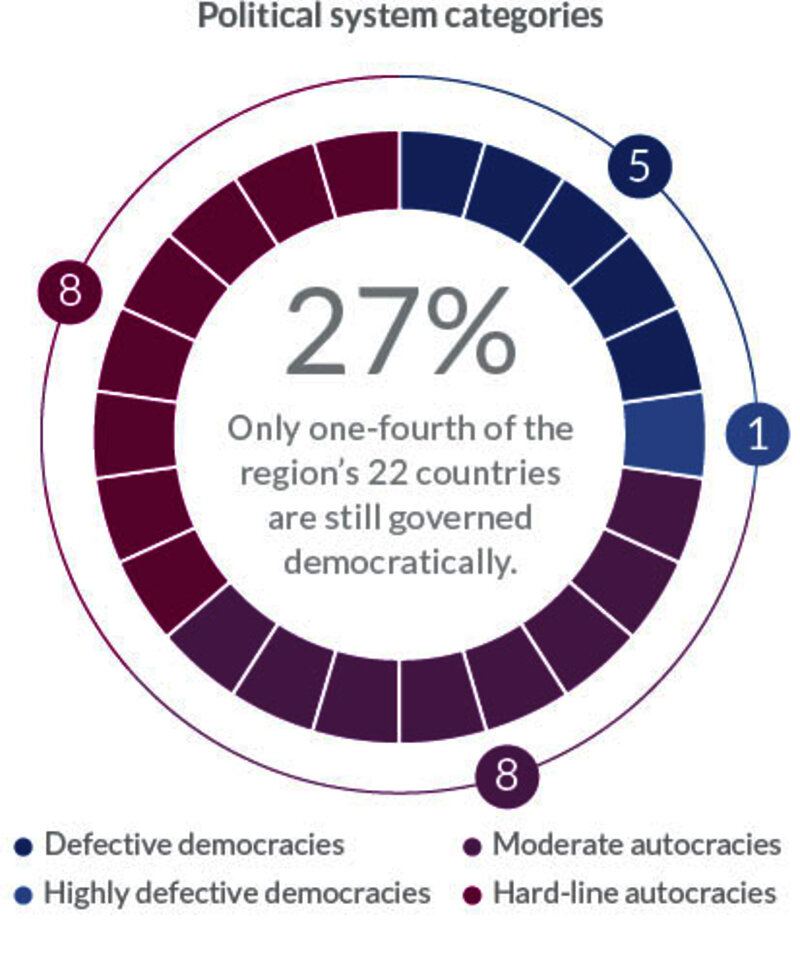

Across West and Central Africa, where 16 out of the region’s 22 countries are now ruled by autocratic governments, the downward trajectory in political transformation continues. Economic transformation has stagnated and remains at a low level. In a changing international environment, governments in the region are gaining confidence as they find alternatives to the support provided by Western countries.

The state of political transformation in West and Central Africa is deteriorating. Seven of the region’s 22 countries have lost more than one point on the BTI’s 10-point scale since 2020. Democratic backsliding is on the rise particularly in West Africa, where only six – as opposed to 13 in 2020 – of the subregion’s 15 countries are still democratically governed.

Two West African countries, Burkina Faso (-1.97 points) and Mali (-1.00 points), experienced significant setbacks in the period under review due to coups and precarious security situations. In contrast, Niger made progress during this period, although the military coup in July 2023 has cast uncertainty on the country’s achievements. Democracy in Ghana is also facing substantial pressure, which is being exacerbated by the country’s economic problems.

Economic development remains a major challenge for the region. While the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic have risen from the lowest category of economic transformation, the overall picture suggests that regional formal economies are functioning to a limited extent. This situation is accompanied by a low level of socioeconomic development. However, as Gabon (+0.36) demonstrates, taking positive steps forward is still possible, even when grappling with such constraints.

Despite all the challenges they face, many countries in the region are gradually asserting greater autonomy within a shifting global balance of power. This involves building and maintaining good relations with a variety of states and international organizations. The reluctant support of African states for the UN General Assembly resolution of March 2, 2022, which condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, was a clear signal to Western countries that they cannot expect to impose their position.

Political transformation

Coups and regressions

The political trajectory in West and Central Africa has been pointing downward for several years. Only a handful of positive exceptions stand out against the region’s growing number of political backsliders. In terms of its democracy status, Niger was the only country to have climbed ranks since the last review period. The list of those countries that have been downgraded is considerably longer: In Ghana, restrictions were recorded on the freedom of expression. Sierra Leone faces criticism regarding the competence of its electoral commission and problems with its registration process for the June 2023 elections. Benin, where Africa’s wave of democratization of the 1990s began, is now under autocratic rule. This negative development was already hinted at in the BTI 2022 report, which highlighted tightening regulations concerning the admission of opposition candidates. These rules, which were applied in the most recent elections, effectively barred key figures in the opposition from running and rendered the elections unfair. Barely half of all eligible voters cast ballots. Guinea-Bissau’s downgrading to the group of autocracies is based on the fact that the separation of powers is under severe pressure. Having undermined the legislative and judiciary branches by positioning himself above the law, the president dissolved parliament in May 2022. During the review period, members of the opposition have been persecuted with the assistance of the military, and dissenters subjected to threats.

The plummeting declines observed in Burkina Faso and Mali are rooted in different causes. The coups in these countries are part of a long list of attempted and successful power transitions in the region, underscoring the frequency with which such changes are brought about through unconstitutional means. During the reporting period, in addition to successful coups in Burkina Faso (2022), Guinea (2021) and Mali (2021), coup attempts took place in Gambia (2022), Guinea-Bissau (2022) and Mali (2022).

The motivations behind these coups vary. Notably, a military takeover in the region does not always run up against opposition. Data from the 2020 Afrobarometer show that 56.2% of the population of Burkina Faso expressed a lot of confidence in the country’s military, while only 31.8% had such confidence in their president. Even in democratic Ghana, 35.1% of the population demonstrates significant trust in the military, compared to just 13.9% in the president, highlighting the diminished level of trust in the country’s democratic institutions.

A key challenge for political transformation in West and Central African countries is the weakness of the opposition and the broader party system. A fragmented party landscape (as seen in Niger) and a reluctance to form alliances (as in Mauritania) are common phenomena. Clientelism within opposition parties is also an issue, as evidenced in the Republic of the Congo and Benin.

Freedom of expression and the press vary greatly across West and Central Africa. Whereas in Gambia and Ghana, a high degree of freedom of expression is guaranteed, journalists in Chad work at great risk when covering protests in the country. Following the unconstitutional change of government that brought the president’s son to power, the country’s autocratic institutions seem to be consolidating through the increasing frequency of repressive measures.

Economic transformation

The challenges remain large

In terms of economic transformation, two indicators from the BTI’s Governance Index underscore the severe difficulties faced by nearly all West and Central African countries. The first indicator involves an assessment of conflict intensity. With the exception of the Middle East and North Africa, no other BTI region scores so poorly, on average, in terms of the division of societies into conflict-prone political factions, social classes, and ethnic or religious communities. However, substantial variations exist within the region. For instance, while Gabon is at one end of the spectrum with its very low conflict intensity (2 points), Burkina Faso, the Central African Republic, Mali and Nigeria stand at the opposite end with their high conflict intensity (9 points each). The adverse impact of conflicts, especially when they escalate into violence, on economic and socioeconomic development, is self-explanatory.

The second indicator addresses structural constraints. With the possible exception of Gabon, each country in the region faces fairly high or even very high structural impediments to governance. Constraints in the region include an unfavorable geographic location lacking sea access, infrastructural deficits, skilled labor shortages and climate change impacts, all of which complicate efforts to achieve greater prosperity.

Heightened conflict intensity and massive structural constraints contribute significantly to poverty and inequality across the region. For example, in this year’s BTI, only two countries, Gabon and Ghana, manage to achieve a score of at least four out of 10 points on the scale measuring socioeconomic development. In contrast, 10 states marked by massive social exclusion achieve only one point.

With regard to the state of economic transformation, all 22 countries in the region are either limited (five countries) or even very limited (17 countries), while not one country has achieved a more advanced status. No other BTI region exhibits a similar type of clustering, and no other region faces such a challenging situation in terms of economic transformation.

In states endowed with more abundant resources, structural constraints are frequently compounded by the ills of patronage and clientelism, which hinder the effective utilization of resource revenues for socioeconomic development. We see this in oil-rich Equatorial Guinea, for example, which features “staggering” inequality, according to the BTI country report. While the country boasts a substantial per capita GDP, the highest in Africa after Mauritius and Botswana, its poverty rate reached 67% in 2020. Ghana’s economic woes can also be attributed in part to corruption and mismanagement, which have led to reduced proceeds from cocoa and gold sales. A weakened currency and the government’s inability to control inflation, which exceeded 50%, have also contributed to the problem.

Viewed against the backdrop of these general conditions, Gabon’s relative economic strength stands out even more. The country’s economy rebounded after an economic downturn during the COVID-19 pandemic. The upswing in per capita GDP was facilitated by the combined benefits of the country’s resource wealth and a relatively small population. Gabon also reports moderate progress in its education system, including enrollment rates. In a similar vein, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has made slight improvements to its external trade and fiscal policy, albeit at a lower scale. Though modest, these gains counter the prevailing global trend of escalating erosion in fiscal stability observed in the BTI 2024 report.

Governance

Militarization and uncertain outcomes

The security situation remains tense in several West and Central African states, imposing a substantial strain on the governance capacities of these countries. In four cases, conflict intensity has escalated, namely in Burkina Faso, Chad, Liberia and Sierra Leone. In another four cases, however, we see a decline in conflict intensity: the high-intensity conflict observed in the Central African Republic has eased, as have the more moderate intense conflicts in Guinea and the Republic of the Congo, as well as the low-intensity conflict in Gambia. Violent conflicts driven primarily by rebellion, jihadism and, to a lesser extent, separatism, continue to present significant challenges to various states within the region. Jihadism is taking its toll on the Sahel region in particular, impacting countries like Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger.

Continued militarization within the region could potentially either help to stabilize the security situation or exacerbate existing tensions. The fact remains that all governments in the region – except those of Gambia and Mali – have substantially increased their military spending during the reporting period. According to data from SIPRI, Togo registered an 80% rise in military spending from 2021 to 2022, marking the highest growth in expenditure during this span. Following Togo are Guinea, with 43.3%, and Niger, with 28.9%. Nigeria’s military spending reached its peak in 2021, with an investment of approximately $4.4 billion in absolute numbers, which is 10 times greater than the average expenditure of all states in the region.

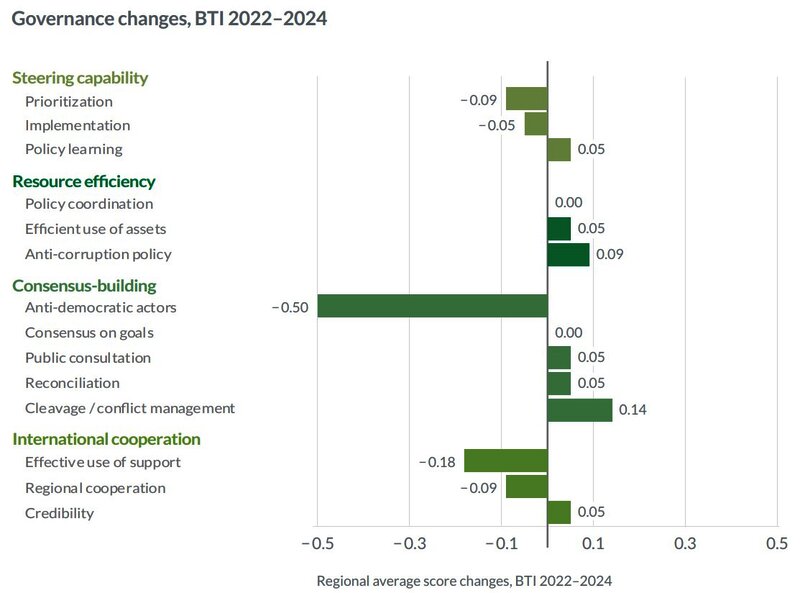

Anti-democratic actors, including the military, parties or companies, can be found in many countries across the region. The capacity of reform agents to manage these forces generally remains weak. Exceptions can be seen in Gambia, Ghana and Senegal. However, the situation is quite different in Equatorial Guinea, the two Congos and Chad. In Chad, under the leadership of the deceased president’s son, military rule has solidified. A protest in October 2022 against the extension of the transitional period, intended to lead to elections, was brutally suppressed by security forces. The circumstances are also challenging for reform advocates in Mali, where coups occurred in 2020 and 2021, leaving military juntas assuming now in power. In Burkina Faso, Mali’s neighboring country, the prominence of anti-democratic actors is doubly apparent due to the two coups that transpired in 2022.

Corruption continues to be a pervasive challenge in West and Central Africa, where little improvement has been recorded in recent years. Liberia serves as an illustration of these stagnating efforts. Although the downward trend underway since 2016 (from 6 to 3 points) has stalled, the persistently low scores recorded for anti-corruption efforts in the country are striking, particularly considering that Liberia was among the best performers in the region nearly 10 years ago. In contrast, the establishment of an Anti-Corruption Commission in Gambia and analogous efforts in Côte d’Ivoire herald positive shifts.

Outlook

All in all, the future looks rather gloomy, with developments in Ghana giving rise to specific cause for concern. The country’s economic situation is strained, and corruption scandals are increasingly eroding public confidence in democratic institutions. In Benin, much hinges on whether the president succeeds in further consolidating authoritarian structures or if the opposition, which is once again represented in parliament, can impede this pursuit.

Conditions in Burkina Faso and Mali are more stark and clear. Although both countries are undergoing transition processes, the security situation remains notably tense. The heightened involvement of Russian mercenaries in Mali, combined with the requested withdrawal of the UN peacekeeping mission from the country and the already planned pullout of certain European states, can hardly be construed as encouraging signs. The potential for further descent into a failing-state scenario cannot be discounted. The same holds true for Burkina Faso.

On the global stage, two interconnected trends come to light. On the one hand, we see a growing dependence on foreign actors, especially authoritarian countries like China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Turkey, which are demonstrating their increased interest in Africa. On the other hand, African actors on the international stage are asserting themselves with greater vigor, signaling a desire to act with greater autonomy in global politics. They aspire to shape policies, as seen in negotiations on climate change, grievances regarding disparities in the availability of vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic, demands for the return of art plundered by colonial powers, or positions taken regarding Russia’s invasion in Ukraine.

Thus, while the ability to select from a range of potential partners undermines Western states’ (inconsistent) efforts to advance democratization, having options also compels African governments to seek cooperation on an equal footing with Western countries.